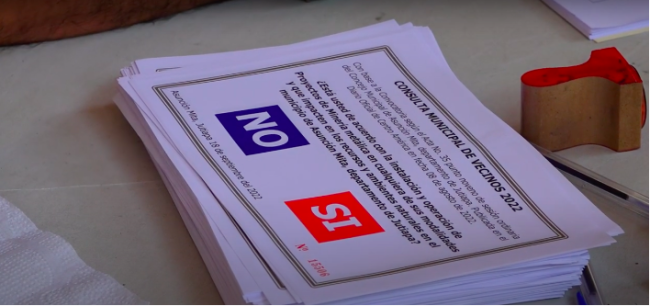

On September 18, 2022 in Asunción Mita, a Guatemalan town near the border with El Salvador, residents lined up to vote in a referendum on mining in their territory. In response to the ballot’s question—“Do you agree with the installation and operation of metallic mining projects in any modalities that impact natural resources and the environment in the municipality?”—89 percent voted “no.” The ballot’s wording reflected the municipality’s right to safeguard the territories within its jurisdiction. However, the joy of this victory was short-lived.

The day after the consultation, the mining company Bluestone Resources, the Guatemalan Ministry of Energy and Mines, and industry groups contested the legality of the referendum. Two provisional injunctions brought by Mita Avanza, the town’s pro-mining association, and by Bluestone Resources’ Guatemalan subsidiary Elevar Resources, also contested the consultation process. Once again, the sovereignty of mining-affected communities and their right to consultation was disregarded, and private interests moved to criminalize grassroots organizing efforts at the forefront of anti-mining resistance. This is the reality faced by land defense movements and environmental defenders in Central America, a reality worsened by the legacy of the pandemic.

In Central America, in the true fashion of disaster capitalism, the pandemic presented mining companies with the opportunity to consolidate an exploitative economic model, while communities opposed to mining faced the erosion of democratic rights and increased state violence. According to Juan López, member of the Municipal Committee for the Defense of Common and Public Goods of Tocoa, a network of local groups dedicated to land and environmental defense in northern Honduras, “during Covid-19, environmental defenders were jailed, we were locked in our houses, while mining companies kept working and profited from the pandemic.”

Central American countries including Guatemala and Honduras have a poor human rights record when it comes to mining, and numerous environmental defenders opposing the industry have been arrested or killed. In the last decade, at least 1,733 people have been killed trying to protect their lands and the environment around the world. According to a 2022 Global Witness report, more than half of these attacks occurred in Latin America.

Extractivism and Resistance in Central America

During the 1980s and 90s, the World Bank began promoting mining as a pathway to development and solution to extreme poverty and the devastating impacts of armed conflicts. The signing of the peace agreements in Central America in the 1990s brought hope for a peaceful transition to democracy. But the young democracies began to crumble in the early 2000s under the weight of neoliberal economic reforms imposed by international financial institutions like the World Bank. Structural adjustment policies sought to facilitate the privatization of state-run industries and services, followed by opening the economy to foreign investment in the areas of communications, banking, and manufacturing. Increasingly these policies also include the concession of large extensions of territory for the extraction raw materials, energy generation, and the monopolization of agricultural commodities for global markets.

Communities affected by mining projects are organizing in opposition against the extractive model as they endure its severe socio-environmental impacts. Mining is an extremely water-intensive industry. Water is used in ore processing and suppressing dust, leading to both water scarcity and water contamination. Mining impacts local communities’ access to water for consumption, irrigation, and cattle rearing.

“Mining companies are the visible drivers of extractivism,” says Pedro Landa, a Honduran activist from the Iglesias y Minería network, an ecumenical space of Christian communities, pastoral teams, and laypeople seeking to respond to the damaging impacts of mining. “But behind them, there are supportive governments in our region pushing for a neoliberal agenda without a care for our environment.”

As anti-mining movements have gained popular support in the region, they have formed strategic national and regional alliances to achieve important victories in regulating and even stopping the installation of mining projects. In Guatemala, three large-scale mining projects were suspended after Constitutional Court rulings determined that they were installed without proper consultation and consent from local Indigenous communities. In 2017, the legislature of El Salvador enacted a historic national ban on all metal mining after a 12-year struggle in which at least seven mining activists were assassinated. The mining company Pacific Rim, later owned by OceanaGold, went on to sue the country in international courts—and lost—over the loss of potential profits. More recently the new government of Xiomara Castro de Zelaya announced in March 2022 that it will ban open-pit mining in Honduras, but it is unclear when the ban will go into effect or how it will affect existing projects.

The Criminalization of Anti-Mining Activists

As land defense movements impact the interests of multinational mining corporations, local governments respond by criminalizing their activities. Efforts to criminalize activist movements range from smear campaigns and threats of violence to using state institutions to bring charges against activists. These charges are often fabricated and carried out in collusion with private interests. “Politicians and the press who ally with mining companies,” explains Julio Gónzalez, a member of the Guatemalan environmental organization Colectivo Madreselva, “accuse us of being anti-development, of being eco-hysterics. They try to stop our opposition by any means.”

The prevalence of grassroots struggles for environmental justice in Honduras and Guatemala is a testament to their resilience. As evidenced in the mining conflicts reported here, even when consultations take place—with great effort and organizational work from communities and organizations—the results are ignored or declared invalid. This sends a clear message: the stance of affected communities who bear the brunt of the environmental burdens caused by mining in their territory is irrelevant.

"Water is worth more than gold" is now the common claim of anti-mining groups in Central America, who have built regional networks of resistance to defend their territories against multinational exploitation. These movements challenge the development models imposed by governments and international financial institutions. In that spirit ACAFREMIN, the Central American Alliance Against Mining, was formed in 2017 by organizations and mining-affected communities from Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. ACAFREMIN has become a key regional environmental justice actor working closely with local defenders to support their organizing strategy, develop awareness campaigns, facilitate the exchange of information, and foster contacts with regional and international allies to enhance the visibility of mining conflicts. Since its inception, ACAFREMIN has also documented and denounced criminalization through articles, press releases, and videos.

The Guapinol Water Defenders

Defamation, misinformation, and smear campaigns have been used to criminalize anti-mining activists and water defenders from the Municipal Committee for the Defense of Common and Public Goods (CMDBCP) of Tocoa, Honduras. The Committee is a network of local groups dedicated to land and environmental defense, particularly of the Guapinol and San Pedro rivers in the department of Colón. The network includes several environmental committees, peasant groups, and the Parish of San Isidro de Tocoa. Especially since 2014, CMDBCP has been at the forefront of protecting water resources.

In August 2018, CMDBCP land defenders established a protest camp to denounce the environmental contamination caused by an open-pit iron oxide mine and processing plant. The project is owned by the Honduran mining company Inversiones Los Pinares, formerly EMCO Mining, which was set up in 2011 by members of one of Honduras' most powerful families, the Facussé. EMCO Mining was granted two mining exploitation concessions in the Carlos Escaleras National Park in 2014 and 2015. CMDBCP also called attention to alleged acts of corruption in the company’s licensing process.

As documented in a report commissioned by ACAFREMIN, after the camp was brutally dismantled, Inversiones Los Pinares denounced 32 CMDBCP members before the Public Ministry with charges of false imprisonment, aggravated arson, theft, and criminal association. Eight Guapinol defenders presented themselves before a court in Tegucigalpa in August of 2019 to contest their arrest warrants. The judge dropped the most serious charge of criminal association but, in a clear lack of due process, the defenders were sent to preventative pre-trial detention. “The defenders are victims of arbitrary detention and unfounded criminal prosecution, stemming solely from their legitimate work defending the right to water and a healthy environment in Honduras,” said Erika Guevara-Rosas, Americas director at Amnesty International.

The case set a worrying precedent in that the Honduran state used unsubstantiated criminal charges and prolonged pre-trial detention to punish environmental defenders. Constant delays and irregularities affected the judicial process of the defenders and their families, leading to accusations of judicial bias. Finally, in February 2022 after two and a half years in detention, the defenders were released when the Honduran Supreme Court reviewed an appeal that challenged the constitutionality of the charges, stating that the defenders should never have been put on trial. A UN Working Group called the detentions “arbitrary” and said the proceedings “breached a number of human rights standards.”

Defending the Right to Consultation in Asunción Mita

Supported by ACAFREMIN and Salvadoran and Guatemalan Catholic organizations, residents of Asunción Mita collected more than 4,000 signatures from registered voters to request that municipal authorities carry out a “Consulta de Vecinos,” a Municipal Referendum in relation to the Cerro Blanco gold and silver open-pit mine in their territory. According to estimates, the mine will extract some 38.4 million cubic meters of water over a 12-year period of planned exploitation, which will affect the local aquifer for more than 32 years.

The organizing commission and the Asunción Mita municipality argue that the binding character of the consultation is based on Article 64 of the Guatemalan Municipal Code, establishing the right of members of the municipality to hold a consultation on issues affecting the community. If 20 percent of eligible voters participate, the results are considered binding. While not responsible for issuing environmental permits, municipalities are responsible for issuing road, construction, and water use permits that could affect mining operations. A reported 27 percent of Asunción Mita residents participated in the vote, therefore meeting the legal parameters of a binding outcome.

Responding to the injunctions levelled against the referendum, local organizations are mobilizing a legal strategy and have presented preliminary briefings arguing that both instances do not meet the legal requirements of an injunction. They also claim that the judicial orders ignore relevant jurisprudence established by previous rulings of the Constitutional Court.

Environmental organizations say they will continue defending the results of the consulta and, if necessary, will take the case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Communities are concerned that arsenic released in the proposed open-pit mine’s gold extraction process can cause toxic leaching and long-lasting contamination of local water sources, a serious concern for communities that depend on agriculture for their livelihood. Local citizens need to be able to exercise their constitutional rights and be adequately informed and consulted for projects affecting their environment, health, and well-being without risk of criminalization

Transnational Networks Strengthen Strategies for Land Resistance

Environmental justice activists work on multiple geographic scales to denounce environmental injustices. Irregular allocation of licenses, lack of free, prior, and informed consent, and the criminalization of activists all took place in the cases of Cerro Blanco and Guapinol. These examples are emblematic of the assaults perpetrated against land defenders across the region. Sharing experiences and coordinated strategies of anti-mining resistance is crucial. According to Jorge Grisalva from the Colectivo Madreselva, “no environmental fight will grow only at the national level. By maintaining a regional vigilance on mining conflicts, we integrate our analyses and see when mining companies use the same violent and repressive methods to criminalize us across Latin America.”

Incorporating lessons learned, mobilizing strategies, and building solidarity between mining conflicts across Central America, ACAFREMIN has become an important organizational platform for anti-mining movements in the region. Shared issues such as transborder mining, collective watersheds, and climate change have generated new and crucial discussions on natural resource protection and sovereignty. ACAFREMIN and its partners envision Central America as a common home and work to protect its land and resources because defense of the environment knows no borders.

Giada Ferrucci is a Ph.D. Candidate in Media Studies specializing in Environment and Sustainability at Western University, Canada. She is a researcher for the "Surviving Memory in Post-War El Salvador" project and consults with the Central American Alliance on Mining (ACAFREMIN).

Pedro Cabezas is an environmental activist based in El Salvador with experience working in Canada, Cuba, and Central America.

Correction: An earlier version of this article cited the number of voters in the Asunción Mita referendum as 7,000. The total vote was 8,385. Corrected Nov 29, 2022.