Leer este artículo en español.

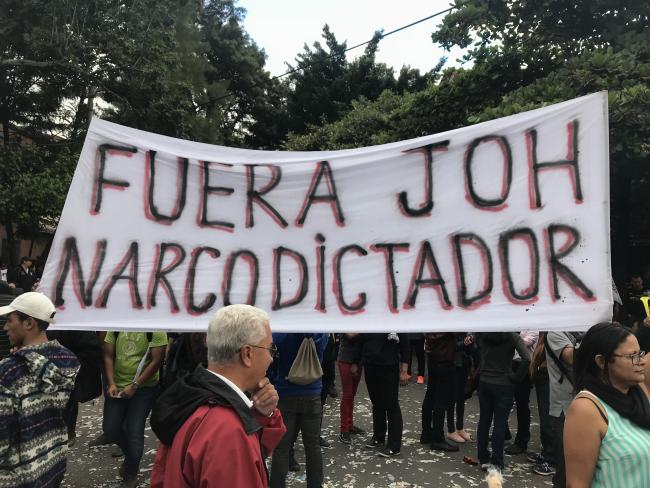

“HA! May he rot in prison, with Pepe Lobo following behind him,” said Gabriela jubilantly. “And we’ll see about Mel too,” she added giggling. I had texted my friend Gabriela the moment I saw the news that former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández (JOH) was convicted of drug trafficking and weapons offenses in a New York federal court on March 8. JOH will be sentenced on June 26 and faces 40 years to life in prison. Gabriela is a Honduran primary school teacher who works a second job to support her four children; she, like many Hondurans, celebrated the news that JOH would spend what is potentially the rest of his life in a U.S. prison cell. However, the consequences of JOH’s two presidential terms and rampant narco-corruption are still omnipresent in Honduras. Gabriela is a pseudonym; Hondurans do not enjoy the same freedom to speak openly about narco-corruption and violence in their country as I enjoy as a gringa.

While Gabriela’s glee about the JOH news was contagious, the hypocrisy of the United States bringing JOH to justice was hard to process. Afterall, it was the United States that had allowed JOH to rise to and maintain power for two terms in Honduras. It was drug consumption in the United States that funded and fueled Honduras’s narco-corruption before and during JOH’s administration. It was the United States that armed JOH’s military forces. Moreover, Gabriela immediately noted that JOH's predecessor, Porfirio "Pepe" Lobo" and ousted former president Manuel "Mel" Zelaya could follow behind him. The current president Xiomara Castro is also Zelaya's wife. It is clear that JOH is merely one dramatic example of a much more systematic problem; a systematic problem which the United States has created and continues to exacerbate in Honduras.

From Banana Republic to Cocaine Republic

Throughout the early 1900s, Honduras was a testing ground for U.S. imperialism and the archetypal “banana republic.” Early U.S. interventions in Honduras to protect capitalist interests entrenched Washington’s influence in the country. As a result, the military became Honduras's “most developed political institution.” By the time Reagan came to office, Honduras had earned the nickname the “Pentagon Republic.”

Narco-trafficking in Honduras pre-dates the Contra War and has long been embroiled with politics and the country’s armed forces. However, the United States’s use of Honduras as a staging ground for its Cold War interventions in Central America—especially during the Reagan administration—bolstered these corrupt alliances. The U.S.-backed Contra War in Nicaragua brought significantly increased U.S. military aid and training into Honduras; this funding often directly bolstered the power of corrupt, narco-elites.

In the early 1980s, U.S. counternarcotics efforts focusing on disrupting trafficking routes through the Caribbean into Florida greatly increased Central America’s importance as a trafficking and transshipment corridor. Meanwhile, U.S. counternarcotics efforts in Honduras were impeded by the United State’s political interests in the country. For example, the DEA office in Tegucigalpa was closed in 1983, a mere two years after opening. Officially the closure was due to budgetary reasons; however, research suggests the true reason was that DEA efforts to combat trafficking in Honduras were conflicting with the CIA’s priorities of supporting the Contras. As part of efforts to arm, fund, and train the Contras, the United States partnered directly with several known drug traffickers. One clear example of this is Juan Ramon Matta Ballesteros, who is credited with linking Colombian narco-suppliers, including the Medellín Cartel, with Mexican trafficking organizations such as the Guadalajara Cartel. Matta Ballesteros was also a close CIA contact and his airline, SETCO Air, received a U.S. state department contract for bringing aid to the Nicaraguan Contras. Matta Ballesteros would eventually end up in prison due to being implicated in the 1985 torture and murder of U.S. DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena. The corrupt ties and networks he fostered while he was a key U.S. ally persisted after his arrest.

With the end of the Cold War and Central America’s civil wars, Central America’s role as a cocaine smuggling and transshipment hub continued to expand. U.S.-backed policy shifts towards neoliberalism throughout the 1990s made Central American states more susceptible to illicit market demands, while at the same time, neoliberal reforms eased the flow of both illicit and licit goods throughout the region.

The Coup & Its Aftermath

In 2009, democratically elected Honduran President Manuel Zelaya was ousted in a military coup. The United States was at least passively in support of that coup and was key in legitimizing the post-coup government. The National Party and Honduran Military’s justification for the coup was that it was necessary to protect democracy since Zelaya was seeking to change the constitution and remain in power. In fact, Zelaya merely was advocating for a democratic vote on a nonbinding referendum to see whether the Honduran population would want to consider amending the constitution to allow for re-election. Moreover, it was the National Party that would actually violate the constitution and push for reelection in Honduras. President Porfirio “Pepe” Lobo and JOH, then head of the National Congress, stacked the supreme court with their supporters. A few years later, in 2015, former President Rafael Callejas of the National Party brought a suit to the Honduran supreme court claiming that the presidential term limits violated his human rights. The court ruled in favor of Callejas and the National Party, enabling JOH’s 2017 bid for re-election.

The United States briefly suspended military aid in the coup’s aftermath. But the reported surge in narco-trafficking that followed the 2009 coup d’état led to increased efforts by the United States to support and undertake militarized counter-drug efforts in Honduras. U.S. reports suggest that trafficking increased because of a power vacuum in the aftermath of the coup. But in reality, the United States helped legitimize political actors who, once in power, were responsible for a surge of cocaine flowing through the small country.

Violence soared in Honduras, making it the most violent country in the world in 2013 in terms of intentional homicides. This violence and chaos of the post-coup era served as the background for a new wave of neoliberal reforms. Under President Lobo, who declared “Honduras is open for business” and subsequently under his successor JOH, extractive industries expanded in Honduras and the country privatized numerous national industries and social services including energy and telecommunications. Privatizations limited poor Hondurans access to basic services, while the expansion of agrobusiness and extractive industries increased violent land conflicts and exacerbated narco-deforestation. Public-private partnerships in Honduras and government contracts to newly privatized industries also proved highly lucrative means of laundering money from the drug-trade and the post-coup period saw a blurring of illicit and licit industries in the country while empowering and enriching their corrupt political benefactors.

Although the general level of violence increased, targeted violence against members of the resistance to the coup and leftists increased disproportionately; resistance to the political and economic interests of the narco-elites and National Party politicians became deadly. And while U.S. security aid was purportedly to disrupt narco-trafficking and improve security conditions in Honduras (in hopes that would stem undocumented migration), in reality it supported Honduran security forces who have been repeatedly implicated in violence against marginalized Afro-Indigenous communities, LGBTQ community members, environmental and human rights activists, land defenders, and peaceful protestors in the country.

Arming Two Sides of a Conflict

While it might seem comical now, at one point the United States touted JOH as one of our greatest allies in the War on Drugs. Former U.S. President and leading Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump claimed that JOH was working “very closely” with the United States, and “stopping drugs at a level that has never happened.” John F. Kelly, head of U.S. Southern Command from 2012 to 2016 and chief of staff for President Trump, called JOH a “good friend” and “great guy.” During the two JOH administrations, the United States lavished counternarcotics aid and funding on Honduras. Reports citing that increased trafficking in Honduras resulted from a power void that traffickers exploited in the aftermath of the coup helped justify this approach. Trafficking in Honduras, however, does not happen despite the state or due to state absence, but rather through the state. And arming undemocratic leaders engaged in narcotics trafficking is not going to succeed in disrupting the flow of narcotics. In addition to being counterproductive to disrupting narcotics flows, U.S. security and counter-narcotics aid to Honduras exacerbates violence.

Through security aid, the United States directly arms violent state actors in Honduras. For example, Julián Pacheco Tinoco, a former military commander and Minister of Security (2015 – 2022), was implicated in testimony in a U.S. court in cocaine trafficking through the country in 2016; he was again implicated in different testimonies in 2017 and 2019, as well as connected to the coverup of Berta Cáceres assassination. Nonetheless, throughout the JOH administration, Pacheco remained the Minister of Security until 2022. During that time, he oversaw the Honduran national police force. As Jake Johnston wrote for the Intercept in 2017: “With hundreds of millions of dollars in U.S. assistance pouring into Honduras’s security forces, Pacheco is one of the most important players in the country’s security and counternarcotics cooperation.” U.S. security aid can also directly lead to guns reaching criminal groups. In an article on arms trafficking in Central America, Mark Ungar reported in 2022 that in Honduras, “a special elite military body sold weapons to organized crime networks, while police report as ‘lost’ the arms that they sell.”

Security aid is far from the only way the United States arms the conflict in Honduras; illicit firearms trafficking is a major issue, but so are our legal commercial arms sales to the region. An estimated 50 percent of guns recovered from crime scenes in the region originate from authorized U.S. exports. In the period after the 2009 military coup in Honduras, the United States authorized an astounding over $1.5 billion dollars of arms sales to the country.

The United States arms both sides of the conflict in the region directly through security aid, commercial arms sales, and our inability to stop the illicit southern flow of weapons—not to even mention the guns leftover from Cold War era.

“Up the noses of the gringos”

In a meeting with Geovanny Fuentes Ramirez, JOH purportedly bragged that he would “shove the drugs right up the noses of the gringos.” However, Hondurans don't have to shove cocaine up gringos' noses. The United States is the world's leading consumer of cocaine and narcotics flows result from demand, not supply—Cocaine consumption in North America is the reason that cocaine moves through Honduras, not vice versa. Without demand, there would be no motivation for supplying the illicit drug. As several traffickers who I interviewed during fieldwork in the country told me: The gringos can arrest as many traffickers as they want in Central America, but there will always still be a steady supply of cocaine given the profit potential created by international prohibition.

The profits from the gringos’ cocaine consumption in turn funds the extensive corruption in Honduras, while U.S. extradition policies have further motivated narco-investment in Honduran politics. In 2012, under U.S. pressure, Honduras enacted constitutional reforms to allow for the extradition of Honduran citizens. Honduran traffickers invest in politics in hopes of having enclaves of protection. By some estimates, 90 percent of Honduran campaign funds come from illicit sources. Extensive narco-investment in politics undermines effective governance and democracy.

Deconstructing the Narco-State

While it is hard to understate the hypocrisy of the United States being the one bringing Juan Orlando Hernandez to justice, there is now going to be a form of accountability for JOH. However, there is no accountability for the United States’s role in fostering narco-politics within Honduras, which began before JOH and continues today.

In 2021, Xiomara Castro won the presidential elections, ending over 11 years of continuous rule by the National Party since the coup. One of her campaign promises was to bring an international commission against impunity to Honduras (CICIH), which would be a critical first step to untangling decades of narco-corruption. A similar commission in Guatemala (CICIG) made significant positive improvements in terms of lowering violence (preventing an estimated 20,138 murders between 2008 and 2019) and increasing accountability, before internal politics and a reduction in funding support from the United States (due to efforts led by Republican Senator Marco Rubio) resulted in its demise. Nonetheless, CICIG shows the potential of these commissions to begin tackling deep-seated corruption and cycles of violence.

In addition to supporting CICIH, the United States also has to reckon with its role in creating and sustaining a narco-state in Honduras. The United States needs to end its failed War on Drugs, which has cost over a trillion dollars, entirely failed in its stated objective to reduce drug consumption, and resulted in countless number of lives lost, both due to increasing violence south of the U.S. border and due to overdoses that could have been prevented through a public health approach. The United States should reconsider its security aid to Honduras, as well as authorized commercial arms sales and take action to reduce arms smuggling. Lastly—at a bare minimum—the United States must urgently reconsider its treatment of Hondurans fleeing from violent, corrupt conditions that the United States has a played a vital role in creating.

Laura Blume is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Nevada – Reno. Her research and teaching focuses on the War on Drugs, organized crime, violence, and Central American politics. Her research has been published in Comparative Political Studies, World Development, and Political Geography.